"Archaic Torso of Apollo" by Rainer Maria Rilke

Let's gather around a sonnet about a crumbling statue

I’m pulling back the curtain on my process for a moment. When writing one of these pieces, I almost always begin by determining whether or not the poem I’m analyzing adheres to some form. For any mid-length poem, I first count to see if there are 14 lines, which is the first indicator a poem is a sonnet. Here is how my draft for this piece looked after conducting this analysis:

Today, I present to you “Archaic Torso of Apollo” by German poet Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by Stephen Miller. This is an ekphrastic poem, meaning it is a poem about a piece of art. As you read this piece, I encourage you to pay attention to the rhyming in this poem–how do the perfect rhymes make you feel (eg torso/low) versus the imperfect rhymes (eg head/inside)?

Archaic Torso of Apollo

by Rainer Maria Rilke

We cannot know his legendary head With eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso Is still suffused with brilliance from inside, Like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low, Gleams in all its power. Otherwise The curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could A smile run through the placid hips and thighs To that dark center where procreation flared. Otherwise this stone would seem defaced Beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders And would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur: Would not, from all the borders of itself, Burst like a star: for here there is no place That does not see you. You must change your life.

Source: Ahead of All Parting: Selected Poetry and Prose of Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by Stephen Mitchell, published by Modern Library.

Rilke begins the poem by focusing on the statue’s head—opening a poem about a statue that is only a torso. The first line of this poem is a concession. It is the only time that Rilke says “we.” He writes, “We cannot know his legendary head / with eyes like ripening fruit.”

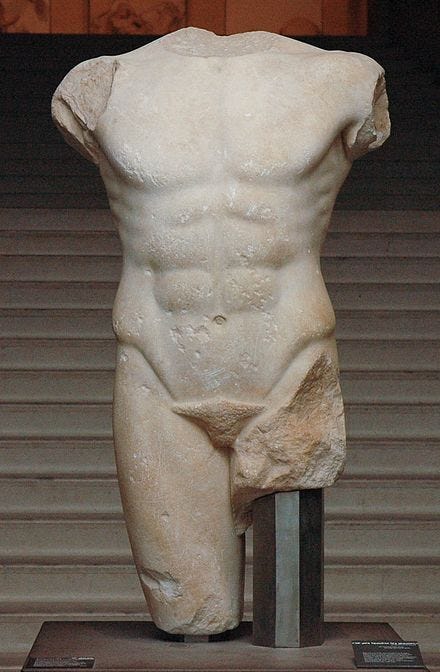

The challenge viewers face with ancient art is that pieces are often missing. Statues cannot survive forever. The heads, the arms, the legs, and the wings are delicate, lost to time. Rilke admits that the statue probably once had a beautiful face with stunning eyes. But we can never know that. We only have the torso. Rilke moves his focus to the torso, telling the reader that despite its lack of head, the torso is as brilliant and mesmerizing as a statue with eyes. He compares the archaic torso of Apollo to a lamp—an object that is “suffused with brilliance” from the inside, like how a light or flame makes a lampshade stunning.

The gaze of the statue isn’t piercing—there are no eyes. Apollo cannot look directly at you. Rilke suggests that the body can see you, though. The brilliance gives the statue a gaze. It is life-like, and even without its head, the statue seems to be as alive as a human.

At this point in the poem, I imagine Rilke at a museum staring at this ancient piece of art. Statues mesmerize me. I cannot imagine the care, the skill, and the time that must have gone into carving statues, especially in a time before modern tools and technology. Below is a picture of the statue that people believe Rilke was writing about. What do you think about the statue? What do you think of its missing head? What about the anatomy that has stood the test of 1,500 years of time?

Where the first lines of the poem are a concession, the rest of the poem is an argument. If not for the gaze coming from the torso:

The curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could A smile run through the placid hips and thighs To that dark center where procreation flared.

Rilke brings the statue to life. He tries to imbue movement and softness to the hard edges of the statue. I love how he poses these descriptions. If the gaze was not radiating from the torso, you would not be mesmerized by the anatomy; you would not feel like the statue could move and take a step towards you, even though it’s missing a head, arms, and legs. He’s speaking directly to you, reader. If the artistry was not so powerful, so full-bodied, you would think this statue was “defaced” with no head. Yet, this is still a work of art. You are still mesmerized. Rilke still took the time to wonder at this statue.

While trying to figure out what to write about this piece, I tried to notice my environment more. This entire poem is a meditation on a piece of art. What would it feel like to wonder at the world the way Rilke does? I have been more present in doing this. On a drive home from school last week, I watched a woman crossing the street. She walked the crosswalk with a friend across a busy intersection. The sun was setting in the city, pouring a soft orange and yellow onto the street and sidewalk. I was waiting at a red light. I watched her look up at the sky, at a skyscraper that lives up to its name. The sun sparkled off the curving windows of the 50+ storeys. She pulled out her phone and looked up. She took a picture, smiled, and put the phone away and continued.

It all happened in a matter of seconds. Why didn’t she stop for longer? What was it about the sun and the sky and the beautiful building that made her stop? What made her take a picture? Has she come back to the picture in the days since? I looked through my camera roll and found times where I did the same thing.

In this poem, Rilke sits in his wonder. When he looked at this half-broken statue of Apollo, he was enraptured. He could feel the gaze of the headless statue and knew that he was looking at a magical piece of art—a feeling that transcends thousands of years. This poem is less a description of a statue, and more of a meditation on wondering. It took me a couple reads to come to this realization, that the beauty of this sonnet comes from standing with Rilke looking at this statue and, for a moment, being in awe. For a minute, I too look at a piece of art sculpted over two thousand years ago and get to wonder at its beauty.

In the end, Rilke describes the gaze of the statue bursting from the borders of the stone like a star. The hard rock cannot even contain all that the statue holds. He writes:

for here there is no place That does not see you. You must change your life.

How does this last line hit you reader? Does it land in your chest or roll off your shoulders? There is a world and artifacts that have lasted longer than you and I can conceive. “There is no place / that does not see you.”

Rilke wrote this poem to you, reader. He opens with “we” to let you know that he is with you, looking at this statue, and sitting in the wonder of its existence and persistence. He is trying to tell you that there is art to be seen, that even a headless statue can gaze at you, that this how people have looked for millennia and maybe we’ve forgotten how powerful a body can be. This poem is an argument. You must change your life. Whether it is to be the statue or to perceive it, I think that is up to you.

If you enjoyed this poem… you can read more by Rilke here, and I highly recommend his Letters to a Young Poet.

If you are looking for a companion to this poem… Rilke wrote another poem about this statue. Read “Plaster Cast Torso of Apollo” here. Which do you like better?

If you want to try writing poetry… pick a piece of art you love and just look at it for a while. Write notes. Bonus points if you can see the art in person!

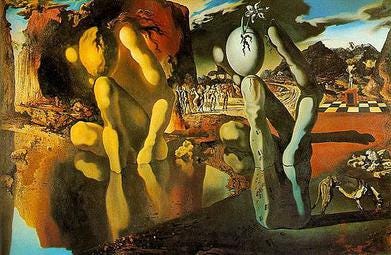

COVER PHOTO: Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937) by Salvador Dalí