Tiny Poem Tuesday, the Moon

Lets gather and read tiny poems about the moon by Sara Teasdale, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Tess Gallagher.

I find it far too easy to forget about the moon. Each day I take out Winnie, my dog, just after the sunrise. I drive twenty-five minutes to school on a dreary highway. I drink cold brew at my desk. I set up experiments that take hours to run. I read and write near a window looking out over campus. I eat lunch, drink water, finish homework, and attend seminars. I gather data from my experiments. I gab with friends and clean my desk. I grow yeast and bacteria. And then I drive home against the setting sun. I pick up groceries, take out Winnie, work, eat, do the dishes, watch a show, read.

But in the evenings, I take out Winnie once again. And I look up at the sky and I see it.

When I see the moon, I wish I could turn off the street lamps and car lights, the red blinking on top of skyscrapers, the fluorescents in office buildings, and the soft LED lamps shining through apartment windows so I could see the world in only the light reflecting off the moon.

Every time I look at the moon I remember that the rock used to be a part of planet earth. Billions of years ago, a Mars-sized object hit the planet and ejected the moon, and for billions of years it has spun and circled its mother planet in an orbit that is one of the most predictable phenomena humans can track.

Then, I forget about the moon for another day.

For Tiny Poem Tuesday, I have gathered pieces about the moon. I think most people have looked at the moon and felt the wonder I tried to describe here. It is difficult to put the feeling into words, and many who try sound cliche. What hasn’t been said about a floating orb that has circled out sky for billions of years? These three poets, in my opinion, succeed in writing about the moon and making me see it from a new perspective. I hope they do the same for you.

(I had Jonny, my husband, edit the introduction to this piece. In an initial draft I described the moon as “beautiful,” to which he said, “Katie, don’t you dare describe the moon as beautiful, that is not who I married.” May this be a lesson to us all to do better than “beautiful.”)

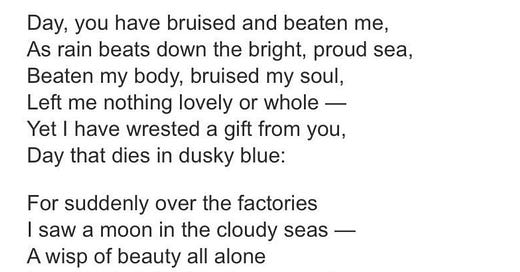

“The New Moon” by Sara Teasdale begins with the speaker addressing the day. She bemoans how it has bruised and beaten her “as rain beats down the bright, proud sea.” This line characterizes both the speaker and the day. The speaker sees herself as someone who is bright, proud, and strong, and the day is relentless and bruising. The day left her “nothing lovely or whole.”

Despite the shortcomings of the day, the speaker has enough energy to wrest a gift from the day, and it is one that she unwraps in the dusky blue of the night sky. Every night brings the speaker the moon. Above the skyline, the speaker sees the moon as a “wisp of beauty all alone.” When I first read this poem, it was at this point where I realized Teasdale was rhyming throughout the piece. The wisp of beauty alone is above a world of stone–gray, cold, and harsh. It makes this poem sound like a lullaby, even though the context is the monotony of an adult life.

At the end of the poem, Teasdale focuses on how the moon’s light softens the world, and in turn softens to people who look at the moon. Despite how harsh a day can be in its bright light with nowhere to hide, there is a miracle sitting in the sky. A maiden moon wakes in the sky above you when the world is quiet. Isn’t that a miracle worth celebrating? How could a person be bitter when there is the gift of the moon waiting at the end of every day?

This is a fragment of an ode written by Percy Bysshe Shelley. “To the Moon” addresses the moon directly, anthropomorphizing it as if the moon could answer our questions. Shelley first asks, “Art thou pale for weariness / of climbing heaven?” The moon, like the sun, rises without fail every day. But isn’t that exhausting? Traversing the entirety of the sky every night? Not only does the moon climb the heavens, but it makes the daily trek alone. Shelley describes the moon as “companionless,” even addressing how far afield it is from the stars we see in the sky. They live and die on different timelines.

My favorite part of this poem is how Shelley compares the moon to an eye. He assumes the reader can make the easy comparisons; they are both spherical, white, and a little mysterious. Shelley looks at the moon as an eye–a joyless eye. What makes it joyless? The moon moves across the sky every night, never stopping to take a break. Every night, the moon appears in a new form–a crescent, a semicircle, a full sphere, or the faint outline of a new moon. The moon can never stand still.

Shelley asks the moon if it is tired of “ever changing, like a joyless eye / That finds no object worth its constancy?” And we as readers know there is nothing we can do. Since the time Shelley wrote this poem, the world has sent life to the moon and has given it brief companions. But does that make the moon lonelier, having experienced an object worth constancy to then spend years in between alone? What would Shelley write now?

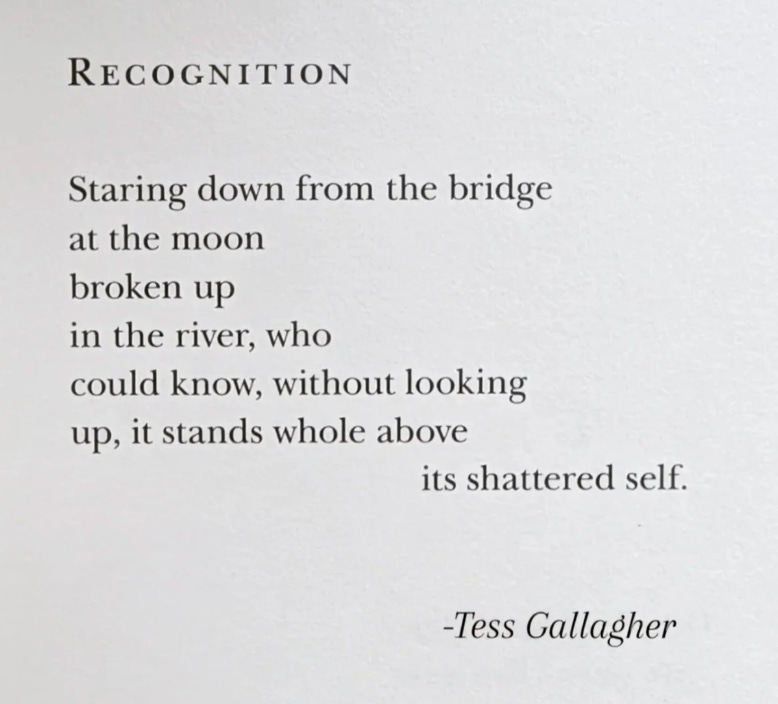

Tess Gallagher writes about the moon in her poem “Recognition.” However, she doesn’t look up to marvel. Gallagher opens the poem, “Staring down from the bridge / at the moon.” I love this opening. It’s unexpected, and for me, it immediately throws me off balance. Gallagher never looks up in this poem. When she looks over the side of the bridge, she sees the moon “broken up / in the river.” In only a few words, Gallagher paints the picture of white ripples over a river. When broken up in these white lines, it’s difficult to put together the image that is distorted in the river reflection.

Distorted is not even strong enough here–Gallagher describes the moon as shattered. The pieces are strewn about, and it would take time to figure out what pieces fit where. Imagine you couldn’t cheat, you couldn’t look up–would you know that the moon was above and whole? What happens when you only look down? It is difficult to see the whole in only shattered pieces.

My favorite part of this poem is how Gallagher breaks up the last two lines:

up, it stands whole above its shattered self.

She physically breaks the line, creating two shards that read differently than the whole. She demonstrates twice how shattering alters how you see something. What’s important is learning how to change your perspective and recognize the pieces for the whole.

And perhaps it’s time for us to try looking down to see the moon.

If you enjoyed this poem… you can read more by Sara Teasdale, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Tess Gallagher here.

If you are looking for a new TV show to watch… I MUST recommend Yellowjackets on Shotime—it has been my favorite show this spring.

If you want to try writing poetry… write about the moon, and try your best to do better than “beautiful.”